With double-entry bookkeeping, you create two accounting entries for each of your business transactions. But why? Are there always two? And where do the entries go? Let’s break it down.

Why is there double-entry bookkeeping?

Double-entry bookkeeping is designed to reflect the greatest truism of business – you don’t get anything for nothing. If something comes into your business, it’s because you gave something up.

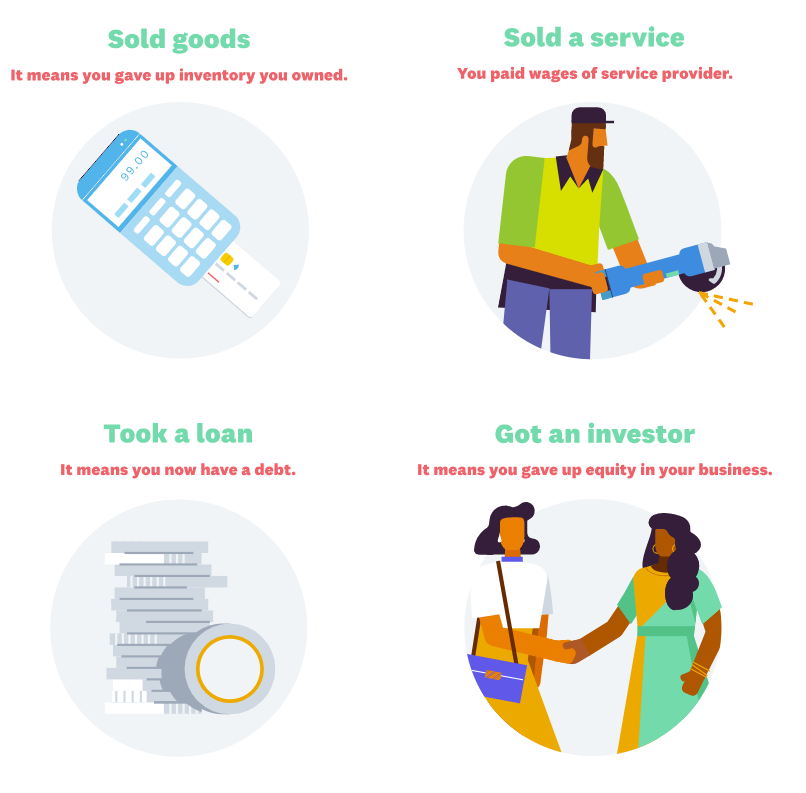

For example, for each of these ways you gain cash, there is an opposite action:

You need to acknowledge both sides of each transaction, and reflect it in your books. And of course you have to make an extra entry to do that – hence double-entry bookkeeping.

Are there always two entries?

Double-entry bookkeeping gets its name because there are at least two entries for every transaction. There may be more. For example, a sale may:

- increase income

- lower inventory

- create a tax liability on the sales tax you collected

And it can get bigger than that. The more complex the transaction, the more entries there are.

How to do double-entry bookkeeping

Double-entry bookkeeping aims to track all the knock-on effects of a business transaction and reflect them in your business accounts. But what does that mean on a practical level?

To get a sense for it, you need to understand a little about:

How the accounts are structured

The books – or ledger – for a business are made up of five main accounts, which are split into groups.

Figure 3, The five main accounts that make up a general ledger.

These accounts are the same for every business – from a freelance worker to a multinational. Let’s learn a little more about them.

What is an asset?

Something of value that the business owns, or part-owns.

Examples: Cash and things that can be converted to cash, including land, tools, accounts receivable and unpaid sales invoices.

What is a liability?

Something (usually money) the business owes.

Example: Loans, unpaid bills, or taxes.

What is income?

Money coming into the business.

Examples: Sales and sometimes interest or dividends on investments.

What is an expense?

Purchases made to keep the business running.

Examples: Inventory, equipment, office supplies and, often, payroll.

Why the accounts are set up this way

These accounts ultimately filter down into your key financial reports.

- The balance sheet

Assets (things owned) – Liabilities (things owed)

= Value of the business.

- The profit and loss

Income (money in) – Expenses (money out)

= Profitability

Where the chart of accounts fits in

A trained bookkeeper can quickly see how a transaction affects the five big accounts, but it doesn’t come naturally to most of us. That’s where the chart of accounts can help. It’s a handy link between daily business activities and the five accounting buckets.

The chart of accounts is a bunch of more meaningful and intuitive categories for your business transactions – like sales, supplies, wages, and loans. When you classify a transaction to a chart of accounts code, it will filter into the right accounting bucket – and ultimately into the right report.

Figure 4, Transactions are coded using the chart of accounts which then feed into the financial reports that reveal how your business is doing.

What happens during a transaction?

The most important rule of double-entry accounting is that nothing ever happens in isolation. When a transaction takes place, you record it in the obvious category of the chart of accounts and then you ask – what else has changed?

Figure 5, Think about where value comes and goes from when you do business.

A professional will see the ripple effect of a transaction immediately. A novice bookkeeper can get the knack of it eventually. Or you can use accounting software and set up rules for how the accounts interact. When you assign a transaction to one account, the software automatically knows what else is affected and records it too.